"The two most important days in your life are the day you were born, and the day you find out why."

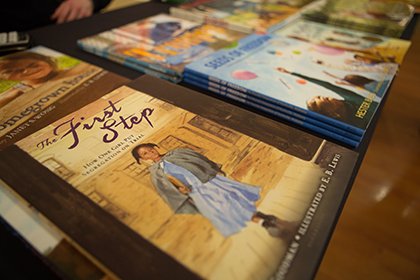

E.B. Lewis and Lesley MFA in Creative Writing faculty Susan E. Goodman discuss their new book, “The First Step: How One Girl Put Segregation on Trial.”

Mark Twain’s statement resonates with award-winning illustrator E.B. Lewis, who believes that finding what inspires each person is essential. It was for him.

“Each one of us is born with this little passion inside of us that is set in motion by things we are exposed to,” said Lewis.

Lewis presented the university’s annual Evelyn M. Finnegan Children’s Literature Collection lecture Wednesday night in the University Hall Amphitheater. He told a packed audience the story of his challenging childhood and his journey to fine arts and illustration. He shared his artistic process, what drives him, and a challenging message for all educators and mentors of children.

At the conclusion of his talk, MFA in Creative Writing faculty member and children’s author Susan E. Goodman joined him to discuss their recent collaboration, “The First Step: How One Girl Put Segregation on Trial,” published in January.

“We are here tonight to celebrate both the creative process and the roles that well crafted books can play in the lives of children,” said Associate Professor Erika Thulin Dawes during her introductory address. She praised Lewis’s considerable talent for understanding both his young audience and the “complexity of our social history,” illustrating books that are beautiful as well as instruments of social justice.

“If you’re doing art for the sake of art, you’re basically not serving society,” said Lewis. “I wanted to be the best artist in the world. Then I realized I wanted to be the best for the world.”

“Help children find what they are good at”

E.B. Lewis has illustrated over 70 books for children.

As a young, poor child in Philadelphia in the 1950s, Lewis competed for attention at home among siblings who teased him, while struggling with dyslexia and a stutter. He failed the third grade and was just plain miserable by the time he entered sixth grade, acting out to avoid the embarrassment of exercises like reading or speaking in class.

Then he was saved. A loving uncle signed him up for Saturday art classes, driving from New Jersey to Philadelphia, every week for six years, to pick up young Lewis and bring him to art class. His uncle was his “superman.”

He recalled for the Lesley audience the first day he entered the art class, demonstrating taking deep whiffs as he described the memory. “Linseed oil and turpentine hit me like a breeze from some tropical island,” he said. “I was pulled in, lured. Kids in there were drawing and painting and playing with clay. The music of Miles Davis playing ‘Bitches Brew,’ and I said, ‘Oh I found my tribe.’”

He can still recall the teasing at school, and the lack of expectations and faith his teachers had in him.

“That can destroy a child,” he said. “How do you rise from that? That’s what this is about,” he said to the audience gathered at Lesley’s Graduate School of Education. “That an Earl Lewis will be in your class – hopefully you will get five of them,” he said with a laugh. “Finding the kids who need that direction, need that help, need that ‘good job’ kind of thing, and ‘you’re not a bad kid’ kind of thing.”

“I needed somebody who cared,” said Lewis. “Help them connect to who they are. Help children find what they are good at,” he implored.

“I’m a storyteller who happens to use the visual language”

From the start, Lewis’s process has involved documenting – everything from cheese-steak shops in Philadelphia to a wheelbarrow heaped with dirt – using his “little pan of water colors” and embracing the “challenge of making the feeling of texture.”

E.B. Lewis delivers the annual Finnegan Lecture.

His fluid and expressive watercolors masterfully convey emotion, moments in history and relationships. He described his artistry as “visual storytelling,” and he considers himself an "artistrator."

When he was first approached to illustrate a book, he declined. But then he learned about the rich world of children’s literature and accompanying fine art. He has since illustrated more than 70 books for children, including “Talkin’ About Bessie: The Story of Aviator Elizabeth Coleman,” the 2003 Coretta Scott King Illustrator Award winner, and “The Other Side,” a 2002 Notable Book for the Language Arts.

He paints subjects such as children being displaced by gentrification in Charlestown, a house on the Underground Railroad through which over 2,000 slaves passed without capture, and a story about the day freedom finally came to the last of the slaves in the South.

“I was working as an illustrator, then I realized that was all wrong. I’m not an illustrator,” he reflected. “In order to do this work right, I’m a storyteller who happens to use the visual language. What I’m doing is mastering the visual language.”

Empower children

Lewis showed images from his “Lotto icons” series, small paintings of children on the face of lottery tickets. He covers the paintings in gold leaf, scratches through the gold to reveal their essence, and frames them “like medieval Byzantine icons,” he said. “There’s something to be said about the immensity of just being human. And so that’s life: Getting us to think and understand the importance of our children.”

(From left) Lesley University College of Art and Design students Stephen

Kunze, Matt Emmons, Kuresse Bolds and Julia Beach meet with

E.B. Lewis and Susan Goodman.

He asserted that teachers should be mindful about what books they assign and how each child in the class may be impacted, citing “Huckleberry Finn” as an example of a book that is damaging in its depiction of people of color. Lewis said children must see themselves represented in stories, and meet characters they can identify with.

When he speaks with groups of children, he encourages them to examine the library books that feature heroes from history.

“Half the people we recognize on the shelf who have done something for society have been through a struggle,” he said, encouraging teachers to have children channel their pain to accomplish things.

“For me, that struggle, I would not give it up,” he said, reflecting upon his childhood. “I would not change a day of it. What I’ve gone through, all those little pieces made me who I am. I had a very tough childhood. Grew up very poor.… Those are the ingredients.”

“The First Step”

In E.B. Lewis’s newest book, “The First Step,” he and author Susan Goodman tell the story of the first case that challenged our courts to outlaw segregated schools, based in 1847 Boston prior to the Civil War.

“Those are the kinds of stories that tug at me,” Lewis said during the Q&A, moderated by Dr. Thulin Dawes. “What an important story about the beginning of this struggle. We’re still in this struggle, unfortunately.”

Goodman said the story has two main characters: Sarah Roberts, the little girl whose family challenged the segregated schools, but also “social justice.”

“I zeroed in on the zig-zagging, lurching nature of social justice,” said Goodman, who teaches in our MFA in Creative Writing program. “That, to me, is a lot of why I wrote the book.”

Through her research, she observed the ways that both sides mobilized and reacted in the tug-of-war over segregation.

“And I guess another really profound idea for me was the realization that if we have certain things we really care about, we better pay attention and we better nurture them, because otherwise they’ll go away.”

For Lewis’s part, he hopes his work in “The First Step” and other books will help preserve and teach history’s struggles and the values that people held tight.

“I realize this is why I was born, to do this work, to create this work that will live on for generations to come,” said Lewis. “I’m not sure I’m choosing the work as much as the work has chosen me.”

The Finnegan Lecture is named for Lesley alumna and children’s author Evelyn M. Finnegan ’48 in recognition of the family's philanthropic support, and organized by the university’s Language and Literacy Division and Sherrill Library.